Eclectic Letters #1 — Kit Wilson

Indian music on drum kit, compositions for player piano, the history of quantification, Dreyfus on Heidegger, Gesualdo, an old gameshow, abstraction, a Polish essayist, good pop, and Niçoise wine.

The editor with a few picks of his own.

Dan Weiss’s Tintal Drumset Solo

Dan Weiss is a phenomenally talented jazz drummer from NYC, who has also been studying for several decades with the virtuoso tabla player Pandit Samir Chatterjee. Back in 2005, Weiss recorded his Tintal Drumset Solo, a transposition of traditional Indian classical repertoire onto drum set. It’s an odd, hypnotically beautiful record.

Conlon Nancarrow’s pieces for player piano

The Mexican experimental composer Conlon Nancarrow (1912-1997) wrote almost exclusively for player piano, an adapted version of the piano that “plays itself” by following what is effectively a very long punch card. Many of Nancarrow’s compositions are deliberately outlandish, making the piano do things no human could physically perform. Here, though, is his more subdued and bluesy Study for Player Piano No. 6, recreated by Jürgen Hocker:

Also pretty interesting is Nancarrow’s house, designed by the Mexican painter and architect Juan O’Gorman:

The Measure of Reality: Quantification and Western Society, 1250-1600 — by Alfred W. Crosby

The Measure of Reality explores the historical origins of quantification in Western society (something that has had, I think, a disproportionate effect on the way we conceptualise reality today). Crosby tells the story of, among other things, the invention of clocks, geometrically accurate maps, precise musical notation, and perspective painting. It’s funny to imagine humans hypothesising about quantification before the appropriate methods were invented. Crosby writes:

What can be measured in terms of quanta is not as simple as we, who have the ex post facto advantage of our ancestors’ mistakes, think. For instance, when in the fourteenth century the scholars of Oxford’s Merton College began to think about the benefits of measuring not only size, but also qualities as slippery as motion, light, heat and color, they forged right on, jumped the fence, and talked about quantifying certitude, virtue, and grace. Indeed, if you can manage to think of measuring heat before the invention of the thermometer, then why should you presumptively exclude certitude, virtue, and grace?

Second, unlike Plato and Aristotle, we, with few exceptions, embrace the assumption that mathematics and the material world are immediately and intimately related. We accept as self-explanatory the fact that physics, the science of palpable reality, should be intensely mathematical. But that proposition is not self-explanatory; it is a miracle about which many sages have had their doubts.

Interesting insights abound, including this on our pre-quantified (or at least pre-fully-quantified) conceptions of time:

Hours, the ancient Middle Eastern units designating the divisions of day and night, were the smallest units with which people commonly concerned themselves. They of course knew there were shorter periods, but they could improvise ways to deal with them: fourteenth century cooking instructions directed novices to boil an egg “for the length of time wherein you can say a Miserere.” Hours, however, were too long and important to guess at. Jesus Himself had said in John 9: 9, “Are there not twelve hours in the day?” (implying twelve for the night as well).

Europe did not straddle the equator, and so the durations of daytime and nighttime changed radically throughout the year. Even so, they had to have twelve hours each. Europeans had a system of unequal, accordion-pleated hours that puffed up and deflated to ensure a dozen hours each for daytime and nighttime, winter and summer.

Crosby writes in a footnote that Yale College was still using a system of variable, “accordion-pleated” hours as late as 1826.

Dreyfus on Heidegger

I can’t say I fully understand Heidegger (who can?), but I got a lot closer watching this video. Hubert Dreyfus’s jittery enthusiasm makes phenomenology almost fun(-omenology? Sorry).

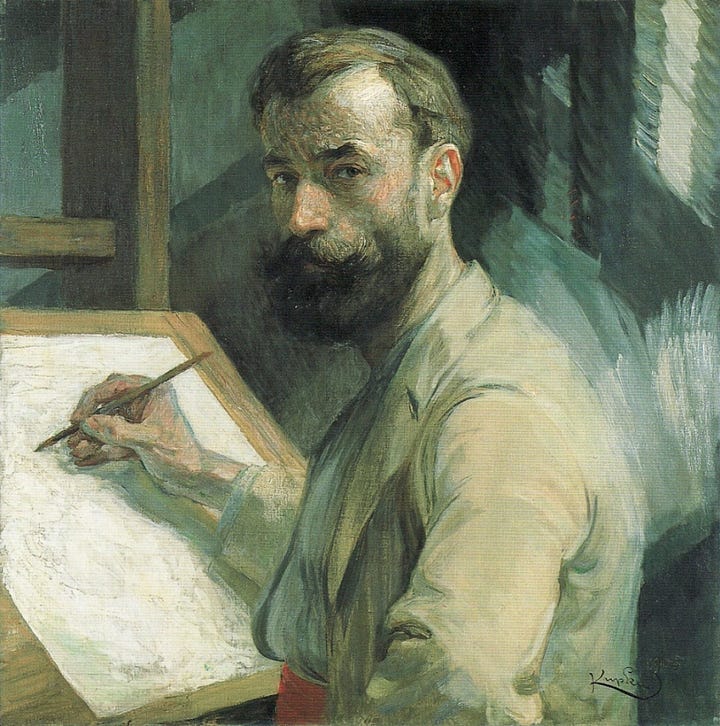

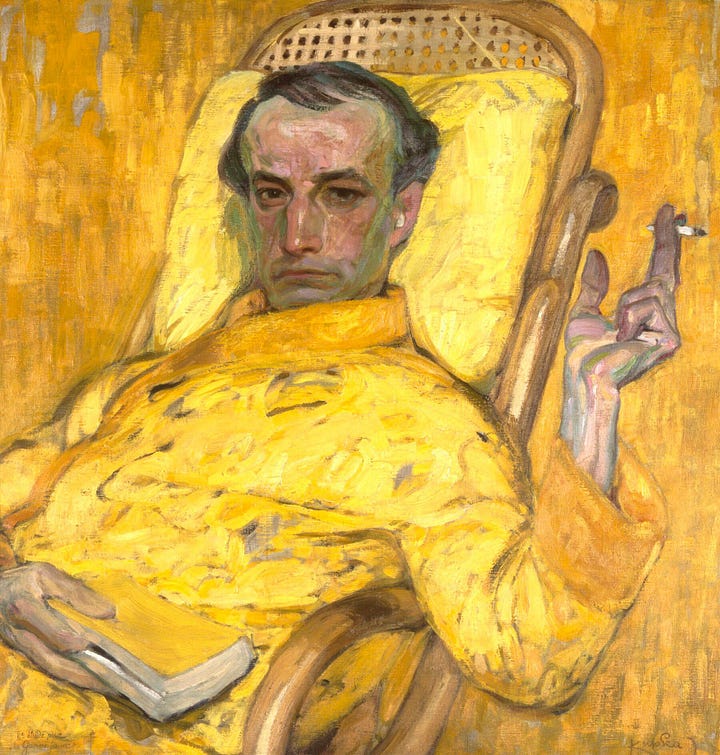

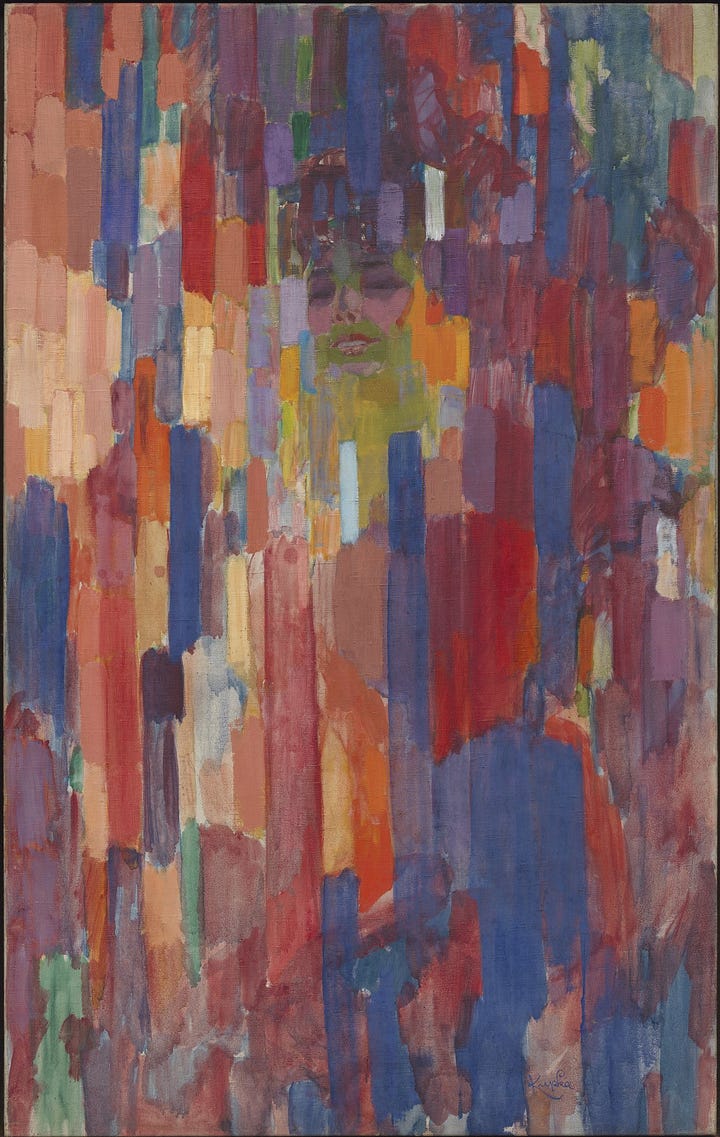

The obliteration of the figurative in four paintings by František Kupka

Fair enough: František Kupka isn’t exactly unknown. Still, while researching this article for Liberties, I spent a long time looking at his paintings, and I was struck by his rapid attack (if that is the right word) on figurative representation over the course of only a few years at the beginning of the twentieth century. The paintings below were made between 1905 and 1913. I am no art historian, but I find it interesting how Kupka almost swallows up the figurative from without: the flat, abstracted elements of his painting gradually surround and eventually suffocate the perspectival, human parts. The bottom-left painting, Mme Kupka Among Verticals, is especially haunting in this respect: we see Kupka’s wife’s face just about still poking out from behind a wall of vertical lines, seemingly any moment about to be smothered once and for all.

Weird Gesualdo

That’d be a good name for a band, wouldn’t it?

I’ve long been fascinated by oddball composers who were harmonically “ahead of their time” (something I’ve written about here). Beethoven’s friend Anton Reicha (1770-1836) could easily be confused for an early twentieth-century composer. Though we know him mostly for his schmaltzier early stuff, late Liszt sounds like proto-Debussy. But there’s something especially touching about the harmonic weirdness of the Renaissance composer Carlo Gesualdo (1566-1613). Listen to his Galiarda del Principe di Venosa below. Those odd chord changes make it feel as if he’s reaching through the vast expanse of history to communicate with you directly — all convention set aside. Shame he was a murderer.

Animal, Vegetable, Mineral?

I recently stumbled upon this gameshow from the 1950s. It’s incredibly low budget — three old chaps sit in a room and have to guess what a series of unusual objects are — but oddly captivating. Bring it back, I say!

Leszek Kołakowski’s essays

Leszek Kołakowski (1927-2009) was one of the great philosophers and essayists of the twentieth century. His essay collection Modernity on Endless Trial is almost certainly the book I’ve dipped back into the most.

A former Marxist turned fierce critic of Marxism, Kołakowski wrote brilliantly on politics, philosophy, intellectual history, and God. His writing has a quality I find quite difficult to sum up — a balance of humour, humility and acidic bite. Perhaps the simplest way of putting it is that he’s one of the few writers I just trust. I could pick from any of his work, but I especially like this passage on the role “history” plays as a modern substitute for religion:

We either internalize history as our way of life or we interact with it in an intimate, quasi-erotic way, as if history were a lady one could seduce. In doing something, I am not simply doing this or that, eating breakfast or visiting an exhibition; in everything I do, I am making history.

What use do people have, or what use did they have, for this curious and unnatural feeling invented by philosophers? The Enlightenment, having pronounced the death sentence on divine providence and then on God himself, rejecting Him as the source of meaning and as the tribunal that could be entrusted with matters of good and evil, soon went on to kill Nature - a substitute for God that provided both moral rules and principles of rationality. History became a substitute for the substitute - a newly discovered infallible foundation on which meaning could be built, and the binding power that could reconstruct a meaningful whole from disconnected pieces and define our place in it.

Historical man need have no historical knowledge or interest in real history; he knows history simply as a reliable and trustworthy legislator. And he believes that history is real: not simply something that once was, but a living being. History “marches on,” like an army; it will “decide if we were right,” like a judge; it will “be the judge of events,” like a scholar. And so on.

This, then, was an attempt to make history the carrier and guardian of all human values, the divine authority that could issue verdicts about good and evil and provide access to the sources of higher reason and meaning.

Palm

One thing the cultural declinists get consistently wrong, I think, is the notion that pop music is getting worse. One day I’ll write about dubious studies, like this, that supposedly “prove” scientifically how bad pop music has become. For now, I’ll just say that there’s loads of genuinely fantastic and innovative pop music being made — you just have to know where (and be bothered enough) to look. Here, for instance, is a great band almost nobody knows, Palm:

Spizzo wines

Something light to finish with. On a recent trip to the south of France, my girlfriend and I took a trip to the outskirts of Nice, where we met Jean Spizzo, a former professor of Italian literature, and now the owner of a small vineyard perched in the hills above the city. We spent a couple of delightful hours walking around the vineyard and tasting the wines (the 2020 red was our favourite). Worth a visit if you’re ever in the area.

Hope you found something of interest!

Kit Wilson is a writer and musician based in London, and the editor of Eclectic Letters. He writes for publications including Liberties Journal of Culture and Politics, the New Atlantis, the Times, the New Statesman, the Spectator, the Critic, and the Telegraph. His website can be found here.