Eclectic Letters #10 — Samuel Rubinstein

Philip Glass's "music with repetitive structures", E. P. Thompson's sci-fi novel, elephants, whales, F. W. Maitland, Norman Cantor’s Inventing the Middle Ages, and scathing academic reviews.

Philip Glass’s The Photographer

The genius of Philip Glass is that he calls your bluff. It has long been observed that sounds sound better to us when they’re repeated, and Glass’s “music with repetitive structures” (he favours this term to “minimalism”) proves just how far this can be stretched.

I don’t know if The Photographer (1982) is Philip Glass’s best composition, but it is his Glassiest composition. And Glass’s music, being the most repetitive music, is the music-iest music; therefore it stands to reason that The Photographer is playing in the Realm of the Forms. It’s a short chamber opera about the eccentric Victorian photographer Eadweard Muybridge, best known for The Horse in Motion and killing his wife’s lover. The libretto lifts mainly from the transcript of his murder trial.

(When I want to give my friends the Glass-bug, I tend to recommend something a bit more accessible, like the gorgeous climax to his otherwise middling 1993 opera Orphée.)

E. P. Thompson’s The Sykaos Papers

The Marxist historian E. P. Thompson, best known for The Making of the English Working Class, also wrote a sci-fi novel — and it’s quite good. The Sykaos Papers is about an alien named Oi Paz who falls down to a near-future version of Britain. On one level the novel is a means by which Thompson gets to relitigate old battles within English Marxism, especially against his most hated foes, the Althusserians — and then to hurl some venom at Thatcher for good measure. On another, it’s a genuinely affecting story about love, death, laughter, anger, and what it means to be human.

The Elephant

I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on a loose translation of the Biblical books of Maccabees by the tenth-century Anglo-Saxon monk Ælfric of Eynsham. (For an introduction to Ælfric, I recommend his “Letter to Brother Edward”, which includes a lengthy digression on the perils of eating on the toilet.)

In 1 Maccabees 6, we hear about the Battle of Beth-Zechariah (162 BC), in which the Seleucids deployed war elephants. This passage posed problems for Ælfric: how would you describe an elephant if neither you nor your audience had ever seen one? He does his best:

An elephant is a massive beast, bigger than a house, all encased in bones beneath the skin, except at the navel, and it never lies down. A mother is with foal for twenty-four months, and they live three hundred years if they are not injured, and people can tame them amazingly for battle.

The detail about elephants being vulnerable at the navel is significant to the Maccabees narrative: Eleazar Avaran, one of Judah Maccabee’s brothers, “came to the elephant, and then ran beneath it; then he pierced it at the navel so that they both lay there, each of them the other’s killer”. Here is a medieval illustration of Eleazar’s martyrdom:

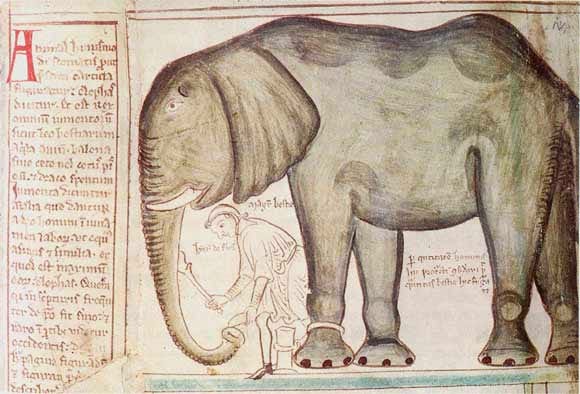

The thirteenth-century monk Matthew Paris likewise had to use his imagination when he drew the emperor Frederick II’s elephant:

But then, as luck would have it, we got an elephant of our very own, maintained in the Tower of London on a robust English diet of beef and red wine. So Matthew Paris got to have a second stab at elephant-drawing, this time from life:

In the wise words of Brooklyn Beckham, “elephants: so hard to photograph, but incredible to see.”

The Whale

My favourite painting in Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum is by a seventeenth-century Dutchman named Hendrick van Anthonissen. The painting itself was only made interesting quite recently, when a beached whale was discovered to have been lurking behind a layer of paint all along.

Like many men, I have a healthy fascination with whales — an itch which Moby-Dick was written to scratch. I got hooked (or harpooned) in Chapter 9, by Father Mapple’s sermon. The 1956 film, starring Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab, is a divisive subject in the Moby-Dick fandom. I like it a lot — in large part because Orson Welles, supposedly while inebriated, does the sermon justice.

Frederic William Maitland

My favourite picture in Oxford, meanwhile, is this one in the Radcliffe Camera, of the legal historian F. W. Maitland.

I like the moustache, the tweed, and the tie; this is how a don ought to look. James Campbell, another great medievalist, apparently told his students to read Maitland’s Domesday Book and Beyond by spending an hour on every page. It’s good advice. Maitland was an intricate and at times slippery thinker, and one of the finest English prose stylists who has ever lived. His writing is often funny. And sometimes it’s surprisingly moving. His 1904 review of Felix Liebermann’s edition of the laws of Anglo-Saxon England inspired my current line of research; and at one point, Maitland compares Liebermann, a German Jew, to the Englishman Sir Francis Palgrave, born Francis Ephraim Cohen:

We believe also that this man [Liebermann], whom we in England can regard as a good representative of what is best in Germany, is one whom what is worst in Germany, the blatant sham science of her Philistines, would ban as ungermanisch. Well, there are fools everywhere; but we in England are not going to dispute the Englishry of our great Sir Francis Palgrave.

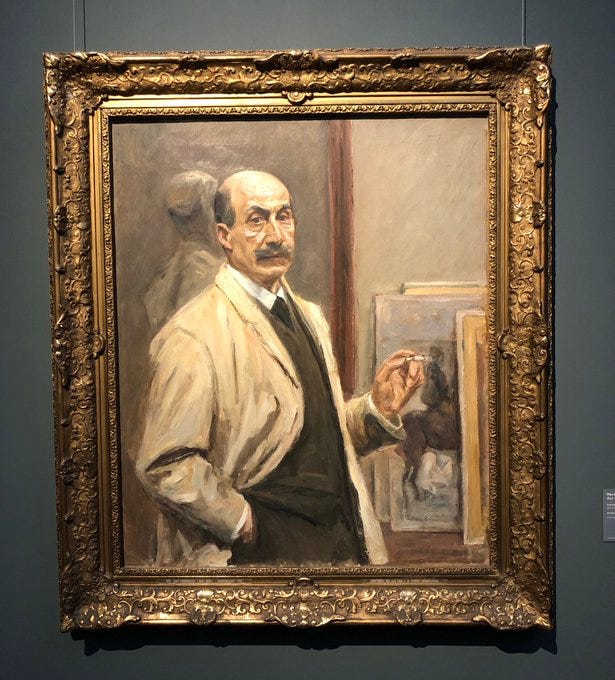

Felix Liebermann, incidentally, was the brother of Max, the painter. I like this self-portrait, which I got to see in Hamburg last year.

Norman Cantor’s Inventing the Middle Ages

A biography of Maitland appears in the first chapter of Norman Cantor’s 1991 book, Inventing the Middle Ages: The Lives, Works, and Ideas of the Great Medievalists of the Twentieth Century. This is a singular book: gossipy, salacious, nasty, at times outright defamatory, often poorly researched, always absurd, and occasionally exceptionally wise. I love it. No stone is left unturned, and no bridge unburned, in Cantor’s profiles of his medievalist colleagues. If you’re interested in C. S. Lewis’s sexual hangups, this is the book for you.

Upon reading it, a very serious German scholar, with the very serious-sounding name of Eckart Grünewald, mused whether Cantor was a “professor at Disney World”. But I think, in his peculiarly Freudian way, Cantor does get to the heart of what many historians are up to. Aside from that, it’s an excellent window into academic pettiness — of which more is to be found in Cantor’s memoirs, published under the characteristically modest title, Inventing Norman Cantor (2002).

Scathing Academic Reviews

In the spirit of Cantorian cattiness, I’m rather partial to critical reviews, having written a few myself. One of my guilty pleasures is staying abreast of academic squabblings; I keep a file on my computer for this express purpose, with Ben Shapiro-style titles (so-and-so DESTROYS so-and-so). It’s a pastime that Twitter chances upon every once in a while. Last year, for example, we were treated to a round of discourse on Maura Dykstra’s apparently terrible book on eighteenth-century China. And more recently, to the Schadenfreude of many, Dan Hicks’s The Brutish Museums was found to have “repeatedly erred in both details and generalisations”.

Here, then, is a handful of further samples, with pointers for those similarly inclined:

D. R. Howlett (1997) on Alfred Smyth’s biography of Alfred the Great:

Those who care about intelligent reception and sensitive transmission of our historical monuments might better pulp than hype this μέγα βιβλίον μέγα κακόν, “a big book, a great evil”.

Stefan Berger responds to Ulrich Muhlack (2001):

Let me start by thanking Professor Muhlack for the good things he has to say about my book, even if they are neatly contained in a single paragraph on p. 38 of his review. Some of the comments are almost too generous to be true. Thus, for example, Muhlack writes: “Anyone wanting to find out about particular authors or schools or facts in general finds reliable information here. No important name is missing; the overall picture is subtle and differentiated.” Yet surely, in a brief book, I am bound to miss out some important names. After all, anyone consulting the index would soon find out that there is no entry under Muhlack.

Dutch–Swiss fisticuffs (2014) over Caspar Hirschi’s The Origins of Nationalism:

Looking at Leerssen’s review in total, I cannot help but deplore a missed opportunity for a good debate. At the same time, I think it was important to respond to his sweeping charges and his pre-print, back-channel propaganda… It seems particularly ironic to me that Leerssen fashions his criticism as a defence of serious historical scholarship but violates basic scholarly standards in several regards.

Mark Thakkar (2020) on two recent translations of Wyclif:

To linger on such niceties would be to fuss over the arrangement of the deckchairs on the Titanic. The looming catastrophe is that Penn’s translations are full of unforced errors that are collectively fatal to the enterprise…

Bearing in mind my criticisms of Penn’s anthology, it is only fair to say upfront that Lahey’s Trialogus is even worse.

...since I already seem to have my tanks on the lawn, it is probably too late to start tiptoeing around the flowers.

“How to Write Fake Global History” (2020), by Cornell Fleischer, Cemal Kafadar, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam, on Alan Mikhail’s biography of the Ottoman sultan Selim I:

We cannot read our fellow historians’ minds, let alone the mind of an early sixteenth century ruler. Why a historian in a respectable university has been possessed to concoct this tissue of falsehoods, half-truths and absurd speculations remains a mystery to us.

And then there’s my favourite subgenre: scathing academic obituaries. Here’s Richard Evans on Norman Stone (2019):

Journalists often described him as “one of Britain’s leading historians”, but in truth he was nothing of the kind, as any serious member of the profession will tell you. The former prime minister, Heath, was wrong about many things, but he was surely right when he said of Stone during his time in Oxford: “Many parents of Oxford students must be both horrified and disgusted that the higher education of our children should rest in the hands of such a man.” Stone is survived by his sons.

Stone would have had no right to complain, having performed something similar on the cadaver of E. H. Carr in 1983.

Samuel Rubinstein is a historian and writer whose articles have appeared in publications including UnHerd, the Critic, the Times, and Engelsberg Ideas.

'Like many men'? I for one am not particularly fascinated by whales – or elephants and other such large animals. Write about rabbits next time. Hath it not been said unto us, 'less is more'?

The conclusion of Terry Eagleton’s review of The God Delusion stands as one of the most blistering attacks ever directed at a reviewed author:

> "But Dawkins could have told us all this without being so appallingly bitchy about those of his scientific colleagues who disagree with him, and without being so theologically illiterate. He might also have avoided being the second most frequently mentioned individual in his book – if you count God as an individual."

Incidentally, this is one of my two favorite reviews of all time. The other is a piece by none other than Jorge Luis Borges, titled Las alarmas del Doctor Américo Castro.