Eclectic Letters #11 — Finn McRedmond

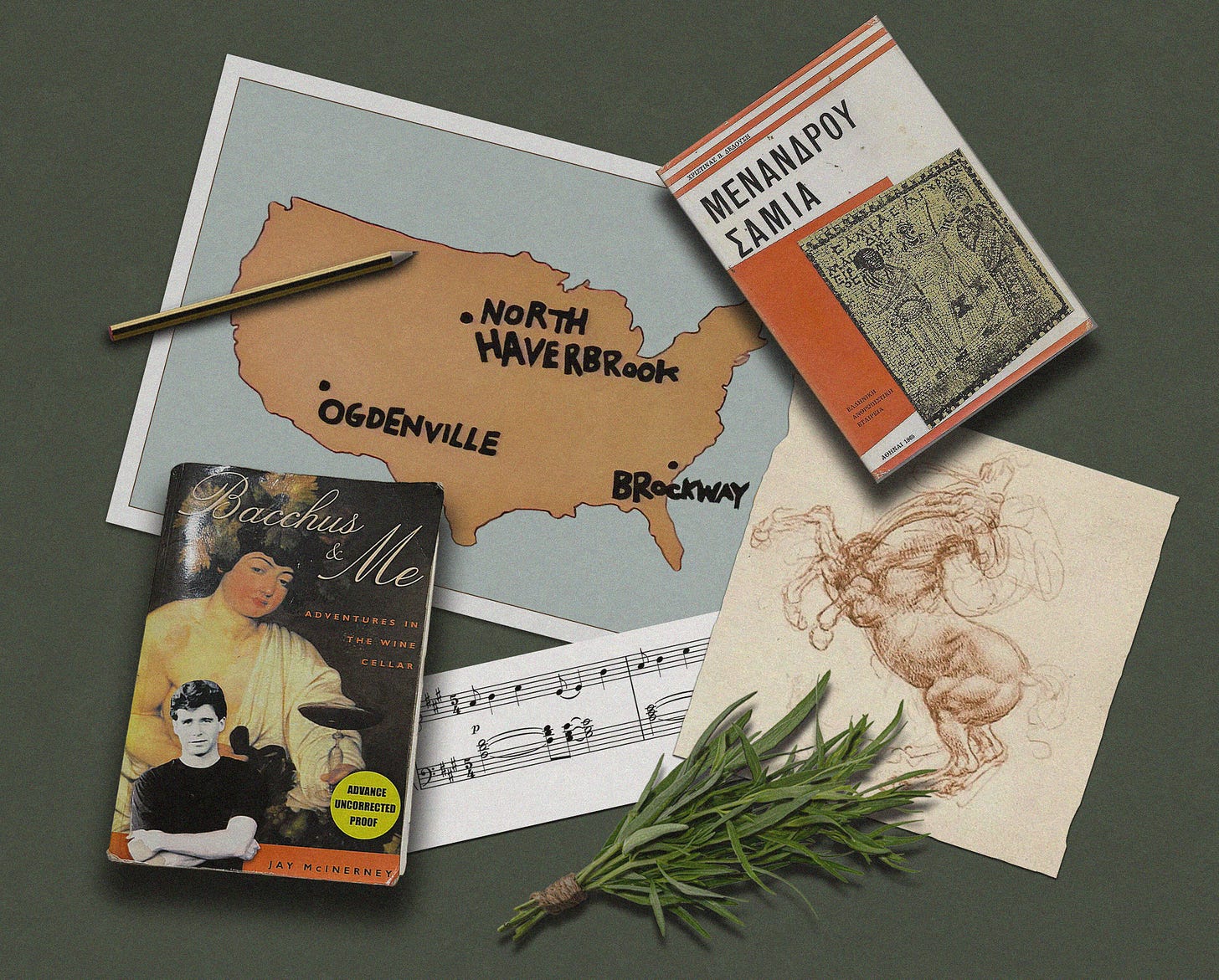

Exquisite equine writing, an avant-garde Simpsons episode, a Menander play, a pop song in 5/4, a literary wine book, Michael Longley's poetry, and tarragon.

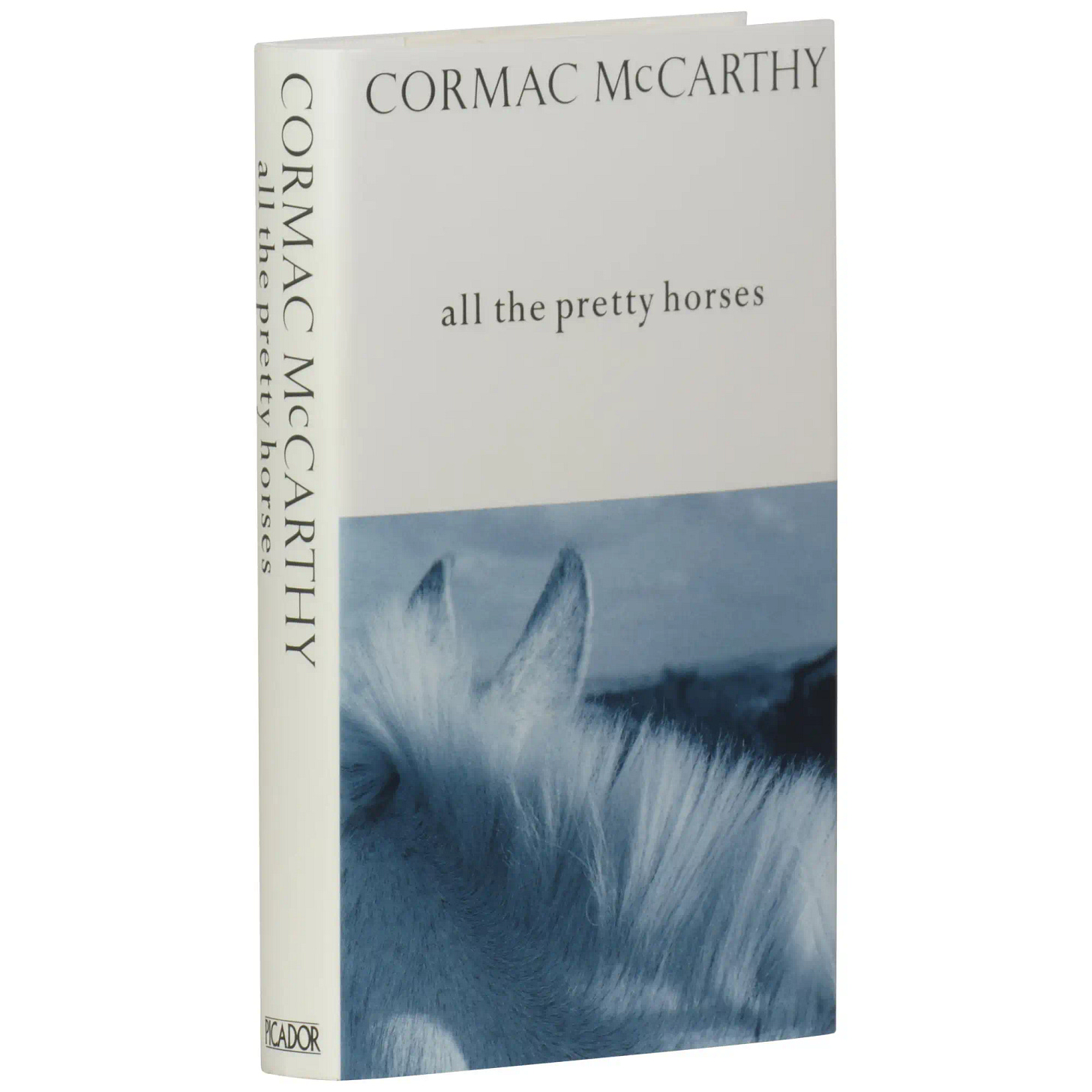

The horses in All the Pretty Horses

A meaningless distinction, perhaps. The horses are the soul of this near-perfect novel: John Grady’s Redbo, Rawlins’s Junior, and Blevins’s nameless bay. I have read plenty of novels or vignettes of novels that contain horses and I don’t think anyone understands the animals in a kind of base, spiritual sense more than McCarthy. Here, in the most consequential passage of the entire book, the boys cross into Mexico:

They crossed the river under a white quarternoon naked and pale and thin atop their horses… Midriver the horses were swimming, snorting and stretching their necks out of the water, their tails afloat behind. They quartered down stream with the current, the naked riders leaning forward and talking to the horses, Rawlins holding the rifle aloft in one hand, lined out behind one another and making for the alien shore like a party of marauders.

I love that — snorting, stretching their necks, the entire story contingent on them. For the mawkish among us, the scene where John Grady and Redbo reunite is affecting, too. And then here is the most McCarthy-esque description of a skull:

There was an old horseskull in the brush and he squatted and picked it up and turned it in his hands. Frail and brittle. Bleached paper white. He squatted in the long light holding it, the comicbook teeth loose in their sockets. The joints in the cranium like a ragged welding of the bone plates. The muted run of sand in the brainbox when he turned it.

What he loved in horses was what he loved in men, the blood and the heat of the blood that ran them.

Not many artists have managed to capture animals well (patiently awaiting the first Great Canine Novel). My phone wallpaper is a picture of Stubbs’s Whistlejacket — a fine painting but not quite right; Leonardo Da Vinci can nearly give a horse an internal life; but only McCarthy has mastered the equine artistic realm.

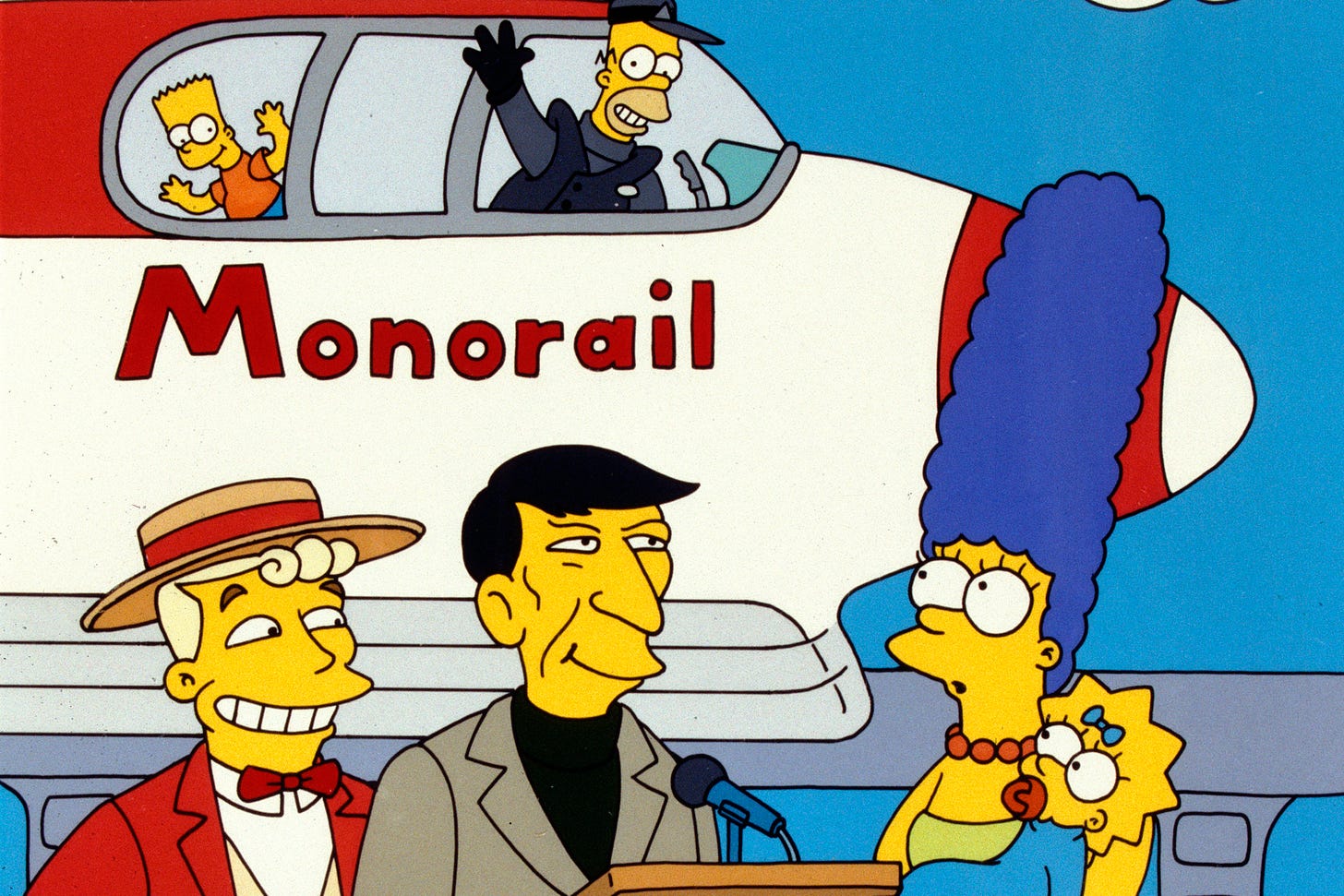

Marge vs the Monorail

Springfield receives an unexpected windfall of cash. How to spend it? Fix the potholes? Don’t be so stupid. A travelling salesman of dubious provenance arrives to convince the flyover town it needs a new monorail system. Maybe my favourite visual gag in the entire series ensues:

This episode pushed the boundaries of what The Simpsons believed it could do. There might have been exceptional plot lines in the past, but the humour was always grounded in the mundanity of lower-middle/working-class Americana. Here is the first successful attempt at entirely unshackling the programme from reality — a musical set piece, an extended opening joke entirely unrelated to the rest of the story, a well-rendered celebrity guest appearance.

But the soul of The Simpsons prevails. Homer’s defining quality is neither his brutishness nor his idiocy, but his optimism (I am not the first to make this observation). As Rory McCarthy points out here, almost all of Springfield’s narrative propulsion happens when this collides with another character’s realism (in this case, the realest of them all: Marge). Monorail is avant-garde but it refuses to corrupt the formula.

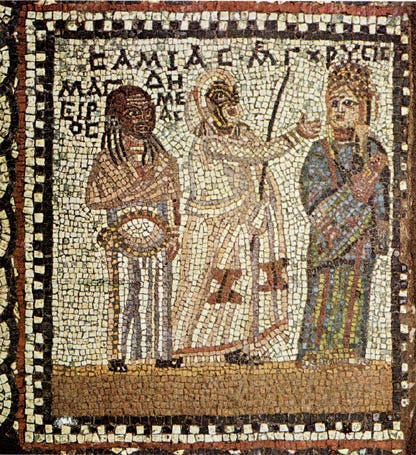

The Samia, Menander

Menander was an Athenian playwright operating around 320-300 BC, and a standard bearer of “New Comedy” (as opposed to his forbear and figurehead of “Old Comedy”, Aristophanes). His work only exists in highly fragmented form. The Samia (the girl from Samos) is one of the more intact plays.

It’s not very funny, at least not on the page. But it’s a classic of the genre: half-truths and misunderstandings drive the action, all oriented around the oikos, while Menander analyses sexual propriety, the father-son relationship, and rich-poor dynamics.

But there is a reason why I love The Samia and Menander more generally. Greek tragedies tend to end rather abruptly: there is the build-up and the tension and the break and the moment of catharsis and then Medea flies off into the sun or Orestes is acquitted. Menander’s fifth acts are always dedicated to what happens after all of that: life goes on even after immeasurable tragedy, so what does the next day look like? In 2025, the instinct still feels modern.

Tarragon

My dad says that tarragon is too aristocratic to even be in my top three herbs and to that I say, “what’s wrong with a little bourgeois aspiration?”

Aniseed has a very unfair disadvantage in life, commonly introduced to children in the form of liquorice. Most well-minded people are turned off forever. But this is a mistake and we shouldn’t cede so much ground to fundamentally disgusting candy. Fennel and tarragon in particular are great aniseedy ingredients and, used correctly, not too medicinal.

Two mistakes with tarragon: using too much and using it raw. It is assertive and can be bitter. But tempered by dairy, it is gorgeous. I have a particular fondness for ingredients that can fuck up an entire meal if deployed badly. It keeps the stakes high.

The time signature in Closure

Okay, OKAY, I know this Substack is called Eclectic Letters and that Taylor Swift isn’t really in the spirit of things. But this song is a deep cut from her under-loved album Evermore and this isn’t really about the song but the time signature: 5/4 over a staccato drum.

Most pop music is written in 4/4 — it gives every verse and chorus a neat and satisfying resolution. Most of Taylor’s music is written in 4/4 too. And lyrically, her songs tend to have a conclusion, a typing up of themes, a call back to the beginning (this is thanks to her country heritage).

But here she is the master at matching content to form. Closure is about the end of a relationship and, er, not finding closure. The 5/4 provides no musical resolution, but tricks the ear into thinking there is more to come, or frustrates you into thinking it should have ended already. No emotional closure, no musical closure. You get it! It’s an odd and unfriendly song — one I think you need to listen to on purpose.

Yes I got your letter, yes I’m doing better [but what if I’m not?] I don’t need your closure [but what if I do?]

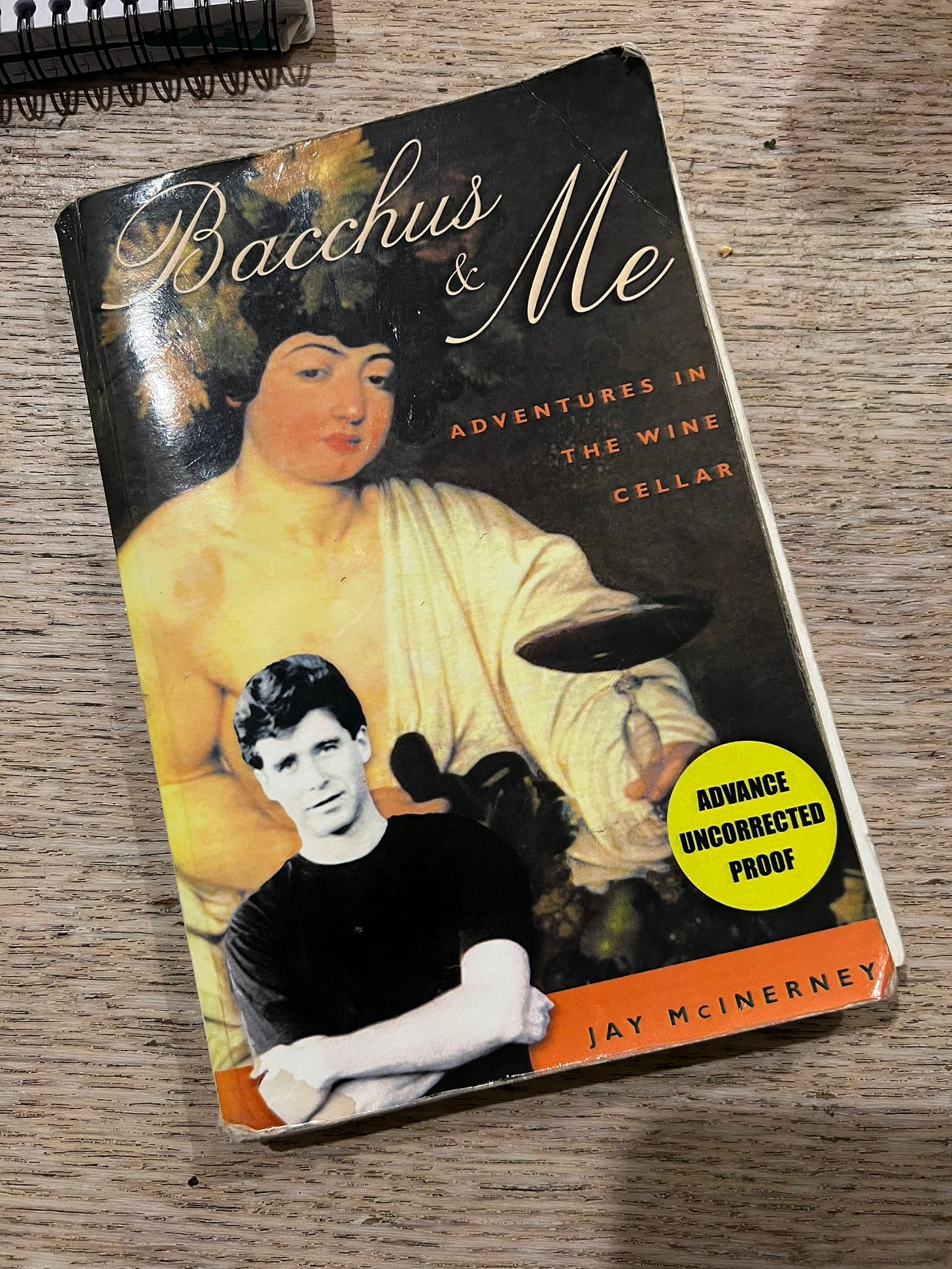

Jay McInerney on wine

I like Bright Lights, Big City. But I think McInerney shines when he writes about wine because almost no one else can do it. The problem is simple: wine writing is either far too technical to be literary (think of your Wine Atlas); or too literary to tell you anything about wine. McInerney gets it right. I am particularly fond of this proof copy of Bacchus & Me (2000).

I am not entirely sure how I came into possession of it but I imagine I stole it from my parents.

Here he is on merlot:

Merlot is the secret weapon of Bordeaux’s Pomerol region, the grape that makes Chateau Petrus among the most powerful, expensive, and sought-after red wines in the world. It’s also the grape responsible for the most insipid red wines of the New World — the white zinfandel of the nineties, Muzak for your palate. The average merlot is so wimpy it’s hard to believe it even contains alcohol.

And on Chianti vs Bordeaux (specifically cab sauv. and merlot):

Like burgundy, Chianti complements a far greater range of food than most wines made from those two slightly arrogant and cosmopolitan grapes.

McInerney recently appeared on one of my favourite podcasts, How Long Gone. He is exactly as you might expect: de haute en bas, with the accent and cadence of a true Californian patrician. About halfway through he tells a very funny story about taking cocaine with Raymond Carver.

Ceasefire, Michael Longley

Last month Northern Irish poet Michael Longley died at 85 years old. I have long been struck by the huge debt the Irish literary tradition owes to the classics, and Longley is no exception. His poem “Ceasefire” compresses the Iliad’s most famous episode, as Priam begs Achilles to return his son Hector’s body. It was published in the Irish Times by then literary editor John Banville in 1994, the week that the IRA declared their own ceasefire.

i

Put in mind of his own father and moved to tears

Achilles took him by the hand and pushed the old king

Gently away, but Priam curled up at his feet and

Wept with him until their sadness filled the building.

ii

Taking Hector’s corpse into his own hands Achilles

Made sure it was washed and, for the old king’s sake,

Laid out in uniform, ready for Priam to carry

Wrapped like a present home to Troy at daybreak.

iii

When they had eaten together, it pleased them both

To stare at each other’s beauty as lovers might,

Achilles built like a god, Priam good-looking still

And full of conversation, who earlier had sighed:

iv

“I get down on my knees and do what must be done

And kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son.”

Finn McRedmond is a writer and editor at the New Statesman, and columnist at the Irish Times. Follow her here.